Bones are a big deal. Fractures, particularly of the hip and spine, can have devastating consequences for both lifespan and healthspan. Consider these statistics from Osteoporosis Canada:

Fractures from osteoporosis are more common than heart attack, stroke and breast cancer combined.

Over 80% of all fractures over the age of 50 are associated with osteoporosis

At least 1 out of 3 women will experience an osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime

Only 44% of people discharged from hospital for a hip fracture return home; of the rest, 10% go to another hospital, 27% go to rehabilitation care, and 17% go to long-term care facilities.

After hip fracture, 60% will require assistance 1 year later, 50% will have some long-term loss of mobility

50% of those with one osteoporotic fracture will have another

28% of women with a hip fracture will die within 1 year

Vertebral fractures are associated with a 10% excess mortality in the year after the fracture, let alone the acute and chronic pain and restriction in movement associated.

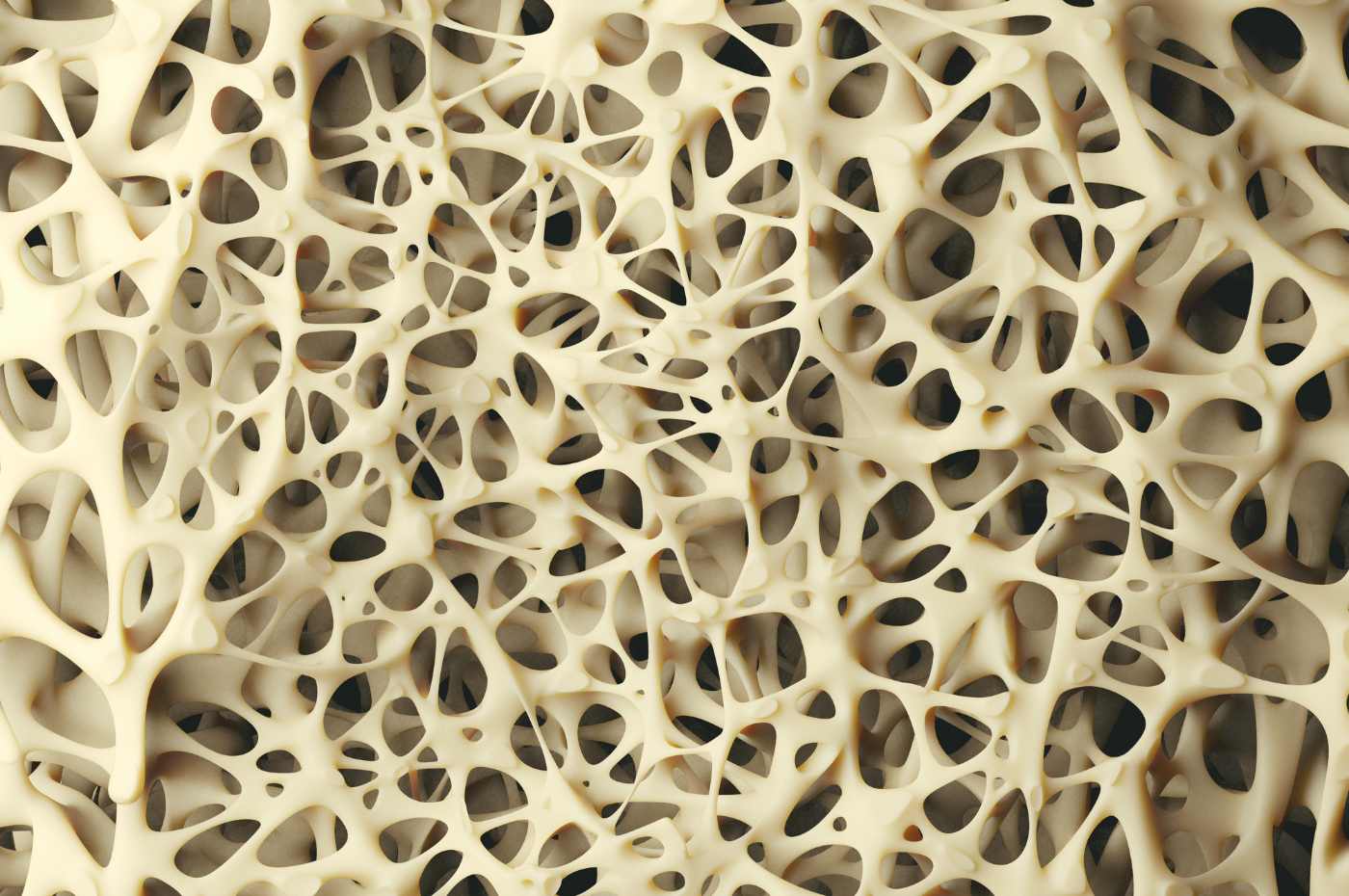

Bone is living tissue, always remodelling

It’s easy to forget our bones are living tissue – with a vascular system, hormone receptors, an outer cortical bone shaft that provides structure to our skeleton, and the spongy trabecular bone that comprises the end/head of the bone. It’s in the trabecular bone where most bone loss occurs. Bone is 70% mineral, primarily calcium and 30% organic matrix – a combination of collagen fibers, carbon, oxygen and water.

Bones remodel daily based on the load placed on them. Under the influence of estrogen and testosterone, bone-building cells (osteoblasts) activate and build collagen bone matrix. Bone breakdown cells (osteoclasts) do the opposite – they break bone down. The density and quality of our bone tissue is a consequence of this hormone-choreographed bone-building vs bone-breakdown cycle.

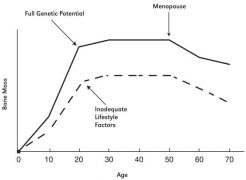

Bone building dominates in childhood and adolescence. Bone mineral density doubles from age 8 to age 20. Through the 20’s, bone building slightly outpaces bone breakdown.

Women reach peak bone mass around age 30 and maintain a relatively stable plateau until menopause when bone mass rapidly declines, with an average annual loss of about 2% beginning 1 to 3 years before menopause and lasting 5-10 years.

Across the menopause transition, women experience an average loss of 10% to 12% in the spine and hip (1).

By the age of 65 bone loss in women slows slightly, down to about 0.5 % per year. By the age of 80 she has lost, on average, approximately 30 % of her peak bone mass.

If a woman’s peak bone mass at age 30 is suboptimal due to lifestyle factors (sedentary lifestyle, dietary deficiencies, smoking, alcohol), medications, diseases (including eating disorders), the diagnosis of osteoporosis can come earlier in post-menopause.

Source: Based on Heaney et al 2000 (2)

A diagnosis of osteoporosis is made when bone mineral density is low enough to become a substantial risk factor for fractures. And it’s the fractures that affect lifespan and healthspan.

When we speak of bone health, we do so with the intention of reducing fracture risk (particularly of hip, spine, pelvis) and there are many factors (apart from low bone density) that affect this.

Established Risk Factors for Fractures:

Age: At any level of bone mineral density, older postmenopausal women are at higher fracture risk than younger postmenopausal women.

Low Bone Mineral Density: Although low bone density at any site is correlated with fracture risk, the strongest correlation is with hip.

Prior fragility fracture: If you break a bone by falling from standing height or less, slipping on ice for example, this is defined as a fragility fracture. Fragility fractures result from low-energy mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture in strong bone. This is different from high energy, traumatic forces such as fractures from car accidents or falls from a height.

Having had a fragility fracture is the most important and powerful risk factor for having another fracture. The risk of refracture is especially high (4- to 8-fold increased risk) in women with recent fractures (3)

Diseases and drugs: Some diseases can be associated with bone loss and fracture risk including:

-

- chronic inflammatory illnesses (rheumatoid arthritis)

- diseases causing malabsorption (celiac disease)

- hormone diseases including hyperthyroidism, type 1 db, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing syndrome

- Type 2 diabetes

Some drugs can contribute to bone loss and fracture risk including:

-

- glucocorticoids, oral or inhaled steroids (prednisone, betamethasone, cortisone)

- drugs that impair Vitamin D metabolism (phenytoin)

- estrogen blocking medications used in preventing breast cancer recurrence (aromatase inhibitors)19

- Proton pump inhibitors- Omeprazole (Prilosec), Esomeprazole (Nexium), Lansoprazole (Prevacid), Rabeprazole (AcipHex), Pantoprazole (Protonix), Dexlansoprazole (Dexilant)

Falls: Most fractures, including many vertebral fractures, occur after a fall from a standing height or less. As a result, risk factors for falls increase risk of fracture. A previous history of falls, weakness, impaired balance or co-ordination, vision issues, obesity and arthritis can make one more prone to falls.

Body Mass Index (BMI): Bone mineral density in healthy women is strongly correlated with body weight. Thin women have lower bone density values than do heavier women. Whether this increases fracture risk is unclear, as thin women who are lean, active and fit may not be at an increased risk of fracture.

Smoking: Postmenopausal women who smoke are at a 30% increased risk of fracture compared to non-smokers, independent of bone density. (4)

Excessive alcohol intake: Consuming more than three servings of alcohol daily is associated with a 38% increased risk of osteoporotic fracture and 68% increase risk of hip fracture.(5)

Parental history of hip fracture: The strongest component of a family history in predicting fracture risk is a parent’s history of hip fracture. It’s estimated that 50-85% of the variance in bone density is genetically determined (6)

Bone Density Testing

The gold standard bone mineral density test is the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan (DXA or DEXA scan): It’s a non-invasive Xray scan, taking 10 minutes, and using less than 1/10th the dose of a chest x-ray. These x-rays are absorbed differently by bone and soft tissues, fat and lean tissue.

If you’re in high or moderate risk range for fracture, you may be recommended a DXA follow up in 1-3 years. If you’re found to be in low risk range, you may be recommended DXA follow up in 5-10 years (7)

DXA bone density scans provide a T-score and a Z-score.

The T-score

The T score compares the bones of a post-menopausal, mid-life woman to the bones of a young (age 30), healthy, Caucasian woman. T-scores are used to make the diagnosis of osteoporosis in post-menopausal women; they are not reliably applied to pre-menopausal women.

A T-score is on a scale of -2.5 to + 2.5. The lower the number, the lower the bone density.

A T-score between −1.0 and 2.5 is considered to be “normal bone mass”

A T-score between -1.0 and −2.49 is considered to be “osteopenia”, which represents a 10% decrease in bone mineral density compared to young healthy adults

A T-score of -2.5 or lower at the lumbar spine, femoral neck or total hip is diagnosed as “osteoporosis” which represents a 25% decrease in bone density compared to young, healthy women.

The Z-Score

The Z score compares a woman’s bone density to other adults of her age, gender and ethnicity. The Z-score has limited value in postmenopausal women but is the preferred manner of expressing bone density results in premenopausal women.

The normal range for the Z-score is −2 to +2.

A Z score of 0 indicates her bone density is in the middle, meaning 50% of people her age will have higher bone density and 50% will have lower

A Z score above 0 indicates she has higher bone density than most women her age

Likewise, a Z score below 0 indicates she has lower bone density than most women her age.

A Z-score of -2 and a history of fragility fracture is diagnostic of osteoporosis in a premenopausal woman

Assessing fracture risk

Bone mineral density is only 1 risk factor for fracture. In post-menopausal women the T-score is input into a risk calculator. The best known is the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool, established by the WHO. This online calculator combines the T-score with multiple known risk factors – age, height, smoking status, family and personal history of fracture, use of glucocorticoid medication (prednisone, for example), rheumatoid arthritis and alcohol intake.

The FRAX calculator arrives at an estimation of one’s risk of hip fracture, or major osteoporotic fracture (arm, wrist, spine), over the next 10 years. The FRAX risk calculator is appropriate for women aged 50 plus. You can find the version for Canadians online here

The FRAX score stratifies women into high, moderate or low risk for fracture.

Medications to Prevent and Treat Bone Loss

If your FRAX score indicates a 20%+ probability of major fracture or 3%+ risk of hip fracture in the next 10 years you’ll meet the criteria of high risk, and prescription medication to treat osteoporosis may be indicated.

Canadian guidelines recommend treating osteoporosis with prescription medication in postmenopausal women with an osteoporosis diagnosis (defined as T-score -2.5 or lower), or in women aged 65 years or older with T-score values of less than -2.0

For menopausal women who are at risk of osteoporosis and are also seeking treatment for hot flashes or night sweats, menopause hormone therapy (MHT) can be used as first-line therapy for prevention of hip, nonvertebral and vertebral fractures. Estrogen therapy can effectively prevent bone loss, however it is not an established treatment for established osteoporosis. (8)

Alas, no treatment ‘cures’ osteoporosis. They’re there to slow the fall.

When do you get your bone density checked?

The current DXA screening guidelines, per The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, indicate women are eligible for DXA screening if they have 1 major and 2 minor clinical risk factors:

Major risk factors (need 1) include:

>65 years

Vertebral compression fracture

Fragility fracture after age 40

Family history of osteoporotic fracture (especially hip fracture in mother)

Systemic steroid therapy >- 3 months

Malabsorption syndrome

Primary Hyperparathyroidism

Propensity to falls

Appearance of osteopenia on x-ray

Early menopause (before age 45)

Minor risk factors include (need 2):

Rheumatoid arthritis

History of clinical hyperthyroidism

Long-term anticonvulsant therapy

Weight loss >10% of body weight at age 25 years

Weight <57 kg (127 lbs)

Smoking

Excess alcohol intake

Excess caffeine intake

Low dietary calcium intake

Long-term heparin therapy

New Frontiers in Bone Density Screening

Screening for bone density is traditionally reserved for high risk or aging individuals, however detection at this point provides few options for prevention. Women in their mid to late 60’s may not be physically able to actively exercise to the extent required to offset bone loss, and over the age of 60 she’s not likely to be a candidate for menopause hormone therapy (MHT).

What if we were able to screen women in their 30’s, 40’s, 50’s for bone density, similar to the way we screen for other biomarkers such as cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure, blood sugar? If she learned at age 40 that her bone density was lower than other women her age would she be motivated to exercise differently, eat more calcium-rich foods, be more consistent with taking Vitamin D or calcium supplements? Since estrogen is an established first line therapy for prevention of hip, nonvertebral and vertebral fractures, would a peri-menopausal woman who’s having hot flashes, night sweats, and on the fence about hormone therapy want information about her bone density? It could help in her decision making.

There’s a new screening option on the horizon. A portable bone densitometry technology developed in Europe is making its way to North America. It’s called REMS (Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry) and it’s a radiation-free ultrasound scan for assessing the bone condition of lumbar vertebrae and femoral neck (hip). It’s conveniently done in a clinic setting in 10 minutes. In peer-reviewed studies from 2019 to present, REMS has been shown to closely correlate with DXA scan results (12, 13, 14, 15,16), regardless of patient’s age, sex and BMI. While REMS doesn’t replace the DXA scan, it provides an opportunity to monitor bone health interventions between DXA scans, or in younger women who may not yet be eligible for DXA bone density testing. And it’s cost effective at approximately $150/scan. A sample report can be found here.

Lifestyle factors affecting bone health

Osteoporosis has a reputation as “a pediatric disease with geriatric consequences”. The most impact we have on bone health is in childhood, teens, and to a lesser extent, in the 20’s.

It’s during these years that peak bone mass is determined. Ensuring adequate nutrition, particularly bone minerals – Calcium, Magnesium, Vitamin D, Vitamin K – and exercise, particularly impact and weight-bearing exercise sets the stage for strong, healthy bones in youth and beyond.

When a woman hits peak bone mass, that’s as good as it gets. Thereafter, her goal becomes slowing its natural decline.

Exercise for bone health

Exercise for fracture prevention includes those helpful for bone density, but also exercise that enhances flexibility, mobility and balance to prevent falls. Any exercise routine will need to consider physical limitations such as joint instability or pain, as exercise can have side effects (sprains, strains, broken bones), especially in those who are poorly conditioned or frail. A physiotherapist or personal trainer can help guide in these cases. Supervised classes such as OsteoFit are designed specifically for those with low bone density and are performed in the context of a physio clinic or session.

Exercise that builds strong bone is variable, dynamic and progressive. Bones remodel based on the load/weight placed on them, the multi-directional forces they experience, and the impact they need to absorb. An active lifestyle that combines all of these elements is ideal for bone health.

Walking instead of sitting forces us to carry the load of our body weight. This is good. Wearing a weighted vest or heavy backpack while walking provides a variable and progressive load in addition to body weight. This is even better. Lifting weights, progressively lifting heavier is ideal. And within one’s capacity, in the context of everyday life, the benefits of carrying heavy things and performing physical labour can’t be underestimated. And let’s not forget baby-carrying for parents and grandparents.

Running, jumping or skipping adds impact to the mix. To vary or progress, add multi-directional movement. This includes running or hiking on trails where the ground may be uneven, up and down hills or stairs, dancing, gymnastics or playing sports where lateral movement/lunging/shuffling is required – basketball, racquet sports, football, volleyball, soccer, baseball. Again, all done within the context of one’s physical limitations and level of conditioning.

Plyometrics utilize short bursts of power, usually jumping, that require strength, mobility and flexibility – burpees and box jumps for example. These are some of the best forms of exercise for building strong bone.

Swimming and biking aren’t weight bearing, but they generate muscular force and this has been shown to be beneficial for bone (though to a lesser extent than some of the exercises mentioned above)

Yoga, pilates, dancing, training on a BOSU ball are helpful for posture awareness, strength, flexibility and balance. This is important in fall prevention.

Essential nutrients for bone health

Calcium

The recommended intake of calcium in women younger than 50 is 1000 mg/day. In women 50+, 1200 mg/day. Calcium is one of the most common nutrient deficiencies in women, especially health-conscious women who are watching calories, limiting dairy or vegan.

While dairy is the most common source of calcium in the diet, it’s entirely possible to consume enough calcium from non-dairy sources. But it doesn’t happen without intention.

Most plant-based milk alternatives are enriched with calcium, but please read the nutrition facts. An enriched plant-based milk should have at least 30% of daily calcium (300 mg) per cup.

Refer to this Calcium Counter to ensure you’re getting adequate calcium. If not, you may need to consider a calcium supplement. I often recommend women have a calcium supplement at the ready – take it at the end of the day if you haven’t met your daily intake needs. When calculating your calcium intake, always include food sources AND supplements. More calcium is not necessarily better.

Vitamin D

Calcium absorption in the gut is dependent on Vitamin D. It’s a foundational nutrient for bone building and remodelling. Osteoporosis Canada recognizes that to achieve optimal vitamin D status, daily supplementation with more than 1000 IU may be required and that daily doses up to 2000 IU are safe and do not necessitate monitoring/blood testing. If you are diagnosed with osteoporosis, Vitamin D testing is indicated, important and covered through OHIP.

Magnesium

Magnesium is an essential co-factor for Vitamin D synthesis. Food sources include green vegetables, beans, legumes, nuts and seeds and whole grains (up to 80% of the magnesium is removed in refined white flour). Meat, fish and dairy are poor sources of magnesium. Deficiency of magnesium up-regulates bone breakdown and down-regulates bone building. Studies consistently show that lower magnesium levels are related to the presence of osteoporosis, and that 30-40% of menopausal women are magnesium deficient. When looking at studies of magnesium supplementation in dosages ranging from 250 to 1800 mg/day, the consensus shows a benefit both in terms of bone density and fracture risk (9)

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is required for activation of the bone-building protein, osteocalcin. Dietary sources include green leafy vegetables, beans, legumes, lettuce. A report from the Nurses’ Health Study suggests that women who get at least 110 mcg of vitamin K a day are 30% less likely to break a hip than women who get less than that (10). Among the nurses, eating a serving of lettuce or other green, leafy vegetable a day cut the risk of hip fracture in half when compared with eating one serving a week. Data from the Framingham Heart Study also showed an association between high vitamin K intake and reduced risk of hip fracture in men and women and increased bone mineral density in women (11).

Invisible yet Inevitable

Bone is an incredibly dynamic and complex tissue. Amazingly, bone loss isn’t painful. Yet we know it’s occurring, inevitably. Compared to the more dramatic symptoms of menopause it can take a back seat – it’s silent, sneaky and until there’s a notable loss in height or a fracture, it’s relatively invisible. By then, the implications can be impactful on many levels. Keep your skeleton in the spotlight with intentional nutrition, exercise, supplements when needed, bone density screening, and in discussions with your health care team on an annual basis.

References

- Greendale GA, Sowers M, Han W, et al. Bone mineral density loss in relation to the final menstrual period in a multiethnic cohort: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(1):111-118.

- Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B, Looker A, Marcus R, Matkovic V, Weaver C. Peak bone mass. Osteoporosis Int. 2000;11(12):985–1009.

- Kanis JA, Johansson H, Odén A, et al. Characteristics of recurrent fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(8):1747-1757.

- Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. Smoking and fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(2):155-162.

- Kanis JA, Johansson H, Johnell O, et al. Alcohol intake as a risk factor for fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(7):737-742.

- Sigurdsson G, Halldorsson BV, Styrkarsdottir U, Kristjansson K, Stefansson K. Impact of genetics on low bone mass in adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(10):1584-1590.

- Papaiannou, A et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ Nov 23 2010; 182 (17) 1864-1873

- Osteoporosis Canada (www.osteoporosis.ca)

- Rondanelli, M., Faliva, M.A., Tartara, A. et al.An update on magnesium and bone health. Biometals 34, 715–736 (2021).

- Weber P. Vitamin K and bone health. Nutrition. 2001;17:880–7.

- Booth SL, Broe KE, Gagnon DR, et al. Vitamin K intake and bone mineral density in women and men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:512–6.

- Amorim DMR, Sakane EN, Maeda SS, Lazaretti Castro M. New technology REMS for bone evaluation compared to DXA in adult women for the osteoporosis diagnosis: a real-life experience. Arch Osteoporos. 2021 Nov 16;16(1):175. doi: 10.1007/s11657-021-00990-x. PMID: 34786596.

- Di Paola M, Gatti D, Viapiana O, Cianferotti L, Cavalli L, Caffarelli C, Conversano F, Quarta E, Pisani P, Girasole G, Giusti A, Manfredini M, Arioli G, Matucci-Cerinic M, Bianchi G, Nuti R, Gonnelli S, Brandi ML, Muratore M, Rossini M. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry compared with dual X-ray absorptiometry for osteoporosis diagnosis on lumbar spine and femoral neck. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Feb;30(2):391-402.

- Amorim, D.M.R., Sakane, E.N., Maeda, S.S. et al. New technology REMS for bone evaluation compared to DXA in adult women for the osteoporosis diagnosis: a real-life experience. Arch Osteoporos 16, 175 (2021).

- Cortet B, Dennison E, Diez-Perez A, Locquet M, Muratore M, Nogués X, Ovejero Crespo D, Quarta E, Brandi ML. Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (REMS) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in a European multicenter clinical context. Bone. 2021 Feb;143:115786.

- Caffarelli C, Al Refaie A, De Vita M, Tomai Pitinca MD, Goracci A, Fagiolini A, Gonnelli S. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry (REMS): an innovative technique for the assessment of bone status in young women with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2022 Jul 28.